Newport Stories:

Red Cross Nurse

Gwen Brown had been in uniform since she joined the British Red Cross when she was sixteen. She had passed her First Aid and Home Nursing exams but before she could go into hospital nursing, she had to get what they called “hospital experience”.

This is her story.

"It’s easy to practise on people when you know there’s nothing wrong with them, but I needed practical experience so in 1939 I was on the wards at the Royal Gwent Hospital. Because of the German blitz of Poland, all the hospitals in Britain were on full alert because we expected the same thing to happen here. We put up beds everywhere you could. Fortunately they weren’t wanted and we had to go and take them down again!

I spent three months training at the Royal Gwent. When you got your nursing certificate, you could go and buy your uniform. I had mine before I was 17. But they weren’t short of nurses in those days, so not all the trained nurses were needed in the hospitals. A lot of us volunteered to work at First Aid Posts but we weren’t paid.

“There’s our Hitler again!”

There were fixed first aid posts and then there were mobile posts. These were single decker corporation buses – “flat” buses we used to call them. They had all the equipment – dressings, sterilised water, everything. Every time a warning sounded, you were supposed to report for duty at the post. It was usually at night. “There’s our Hitler coming again!” we’d say.

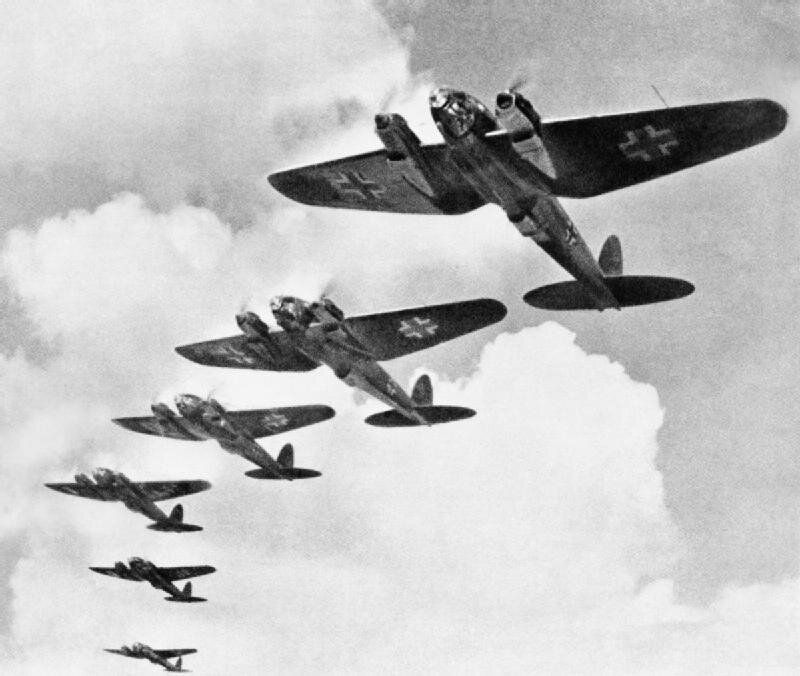

I remember the first German plane, in this road anyway, right at the beginning of the war. We heard this plane coming and everyone came out to see it. There was no warning and it was in the daytime. It came down the street quite low; we could see the pilot. They waved at us and – like mugs – we waved back. We thought it was one of ours. Then we saw the markings on the plane. “My God!” someone shouted. “It’s a German.” And there were no British fighters to see it off. You’ve never seen a street empty so fast in your life! I think he was making a propaganda film, myself – “The British welcoming the German air force.”

Later we got a lot of what we called “nuisance raids” on their way up country to the Midlands. As soon as enemy aircraft were spotted the dock lights would go out, even before the warning sounded. A neighbour from down the road would knock the door and say to my mam, “Mrs Brown, the dock lights have gone out!” When those lights went out, you knew there was going to be trouble. Very often I was at the post before the warning sounded.

They used to let off tear gas in Newport to make people carry their gas masks. Suddenly your eyes would be streaming and you knew they’d let off the gas.

There was a big search light on the Transporter Bridge and Belle Vue Park had a barrage balloon tethered above it. It was nicknamed “Waltzing Matilda”. And there was a very big anti-aircraft gun round the back of St Paul’s Church. The gun used to be moved around; it must have been on some sort of trailer.

There was an Italian prisoner of war camp, down Lighthouse Road. They used to come into town shopping without any guards. The Italian prisoners didn’t want to escape; they certainly didn’t want to go back to war in Italy.

Forge Lane was a very important place during the war. It was full of army vehicles, packed tight. Convoys came in every day and were collected together at Forge Lane. At night they were moved down to the docks and shipped to France, so nobody saw them. Old Lord Haw Haw used to say in his broadcasts, “Hello, Newport! We will meet in Forge Lane tonight!” But they never did hit the Lane.

Some of the worst damage was caused by three sea mines. He was laying sea mines outside Newport Docks and was chased off by our fighters, so the mines dropped on Archibald Street, Belle Vue Park and Ridgeway. The worst was Archibald Street because it came down among the houses.

We laughed about it in the end though when a tree from the park was blown over Waterloo Road and landed on the house opposite us. There it was - this great big tree sticking out through the top of the roof. We took things as they came – we weren’t frightened or surprised by anything.

On the 13th September 1940, there was a night alarm. I was outside my house, number 15 Coldra Road. It was dark and the plane came from nowhere, up the street. Suddenly it was there, on fire, dragging the barrage balloon behind it, pulled away from its moorings. We heard the crash in Stow Park Avenue but we knew we couldn’t go up there. It was a sight to see.

The plane had been laying mines outside the Docks and had been damaged by British fighters. It wanted to land in Tredegar Park but was caught by the cable of the barrage balloon. The pilot had bailed out and his parachute was caught in a tree in Queen Street outside the British Legion. They had to cut him down. He was not very badly hurt and he was taken to the Royal Gwent because we didn’t have a military hospital in Newport at the time.

The Home Guard went round the air raid shelters that night looking for the three crew men. They frightened people to death because they went in the back way through people’s gardens and burst open the shelter doors. All the people inside could see was soldiers with rifles with bayonets fixed and steel helmets. They didn’t know who it was.

The next morning no one could get through because Stow Park Avenue was cordoned off, but I could because of my uniform and I saw the crashed plane.

The doctor wouldn’t allow us tell the pilot that his crew was dead. He was only a young man and when he eventually heard, he cried like a baby. He wasn’t a Nazi. He was a very nice fellow and spoke very good English. Afterwards he was moved to a prisoner of war hospital up country.

There was a big difference between the Nazis and the proper German army and air force and at St Woolos, we could always tell the difference. Ordinary German soldiers we had no trouble with. The Nazis on the other hand, as soon as the back doors of the ambulance were opened, they’d spit at the doctors. I’ve seen it done. But we treated them all the same.

When the Second Front opened, they cleared the old workhouse at St Woolos to be a military hospital, with one ward for prisoners of war. Before then, the wounded British soldiers were treated abroad.

I was put straight into St Woolos Hospital on the night shift as a paid Red Cross nurse. At St Woolos the wounded soldiers usually came in about 1.00 a.m. We’d get a warning about midnight, “Expect a convoy!” They’d come in every week, sometimes twice a week.

St Woolos had 33 beds on two floors with just a nurse and a staff nurse on night duty. I worked with Staff Nurse Sharp. We worked long hours. The night shift was 8.00pm to 8.00am but if you were treating a patient at night, we had to wait until the doctor had seen them in the morning before we could pass them over to the day staff. Sometimes we didn’t finish until 10.00a.m. and 9.00am was an early finish.

About 7.45 one morning, a patient asked me to look at his leg which was in a plaster cast. “It feels wet around the ankle”, he said. “I’ll have a look”, I said. I pulled back the bedclothes and the bottom of the bed was all blood. I called the staff nurse who sent for the doctor but he couldn’t come until 9.30a.m. or a quarter to ten. The patient was haemorrhaging. We just had to wait. You stayed until you’d finished what you were doing, no matter how long it took.

I’d go to bed at 9.00a.m. and was up at 1.00p.m. however late I’d worked. I used to get Tuesday and Wednesday nights off. The day staff had a couple of hours off during the 12-hour shift, and sometimes, a long weekend. We didn’t get any time off during the night shift – after all, there was nowhere to go at 12 o’clock at night. On Tuesdays when I had the night off, I’d go and help at the YMCA army canteen. I used to help organise the dances for the troops who used to get free tickets. When I’d finished, I used to go in to the dance.

Before the D-day landings, there was a big American army camp at Caerleon. I didn’t like them. They were a flipping nuisance; they were very bigheaded. They used to go into the pubs and say to the bar maid, “A pint of beer, miss, as quick as you got out of Dunkirk.” And there were Dunkirk men there, in the pub. You didn’t dare walk past the doors of the pubs at night because of the bodies being brought out after the fights.

One told me off at the YMCA for dancing with an American coloured boy. He tapped me on the shoulder and said, “We don’t allow white women to dance with black men.” Did he get told off! He knew whose country he was in, by the time I’d finished with him!

The black Americans were very polite, much more gentlemanly than the white. We had Indian troops, and the Ghurkhas were lovely. And we had the Australians and the Canadians. Newport was like one big barracks. You name ‘em, we had ‘em.

I suppose we were pretty lucky in Newport; apart from the sea mines there wasn’t very much damage, mostly just windows and doors blown in. There was an elderly couple living down our street and my mother took them each a cup of tea after a raid. She could hardly walk down the street with the broken glass. But do you think the old girl would take the tea? “We’re not having that,” she said. “You haven’t brought any saucers!”

My father was an engine driver at Ebbe Junction. I had a very good life as a youngster; I used to spend three or four months every year in London. (Then I’d come home for a rest!”)

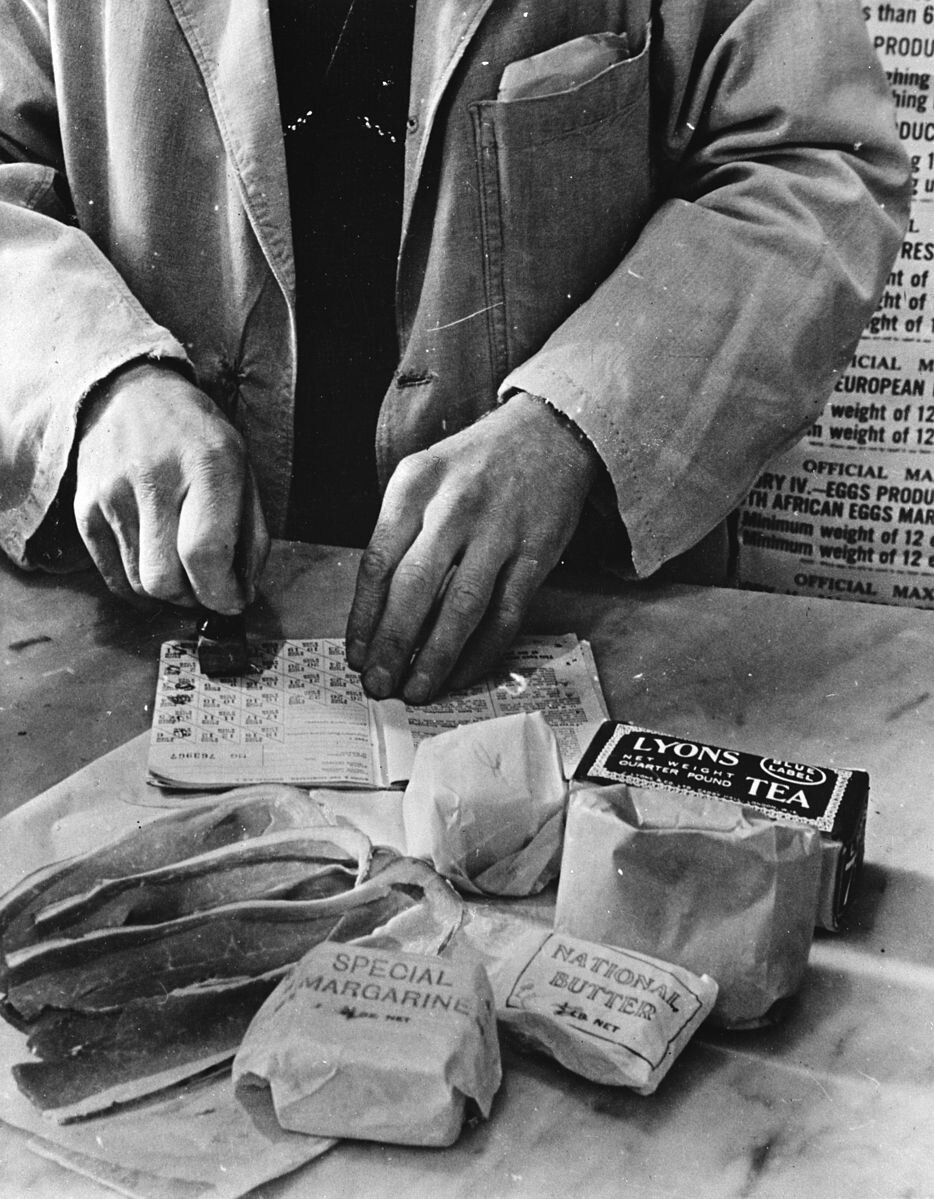

During the war, we managed all right. We’d go up to town and if you saw a queue, you’d join it, no matter what it was for. You wouldn’t pass a queue. If you didn’t want it, whatever it was, a neighbour would. They’d buy it off you for what you paid. We were fortunate because my father had an allotment over the other side of the railway, back of Caerphilly Road. So we had potatoes and vegetables to add to those we could get from the shops and we could always pass things on to families with children.

Even now I’m 84, I’m still on the emergency callout list for the Red Cross."

- Gwen Cook (née Brown), 2004