ROF Stories:

Democracy Marches

William Holt was born in Yorkshire in the 1890s. Largely self-educated, he had fought in the First World War. He became a Communist following a visit to Russia after the Revolution. In the 1930s, he acted as a newspaper correspondent during the Spanish Civil War and was later enlisted by the BBC as a Second World War broadcaster with a distinctive Yorkshire accent.

This is his story.

Overseas North American Transmission: MAY 20th/21st, 1941: 0200 GMT: 0400 DBST.

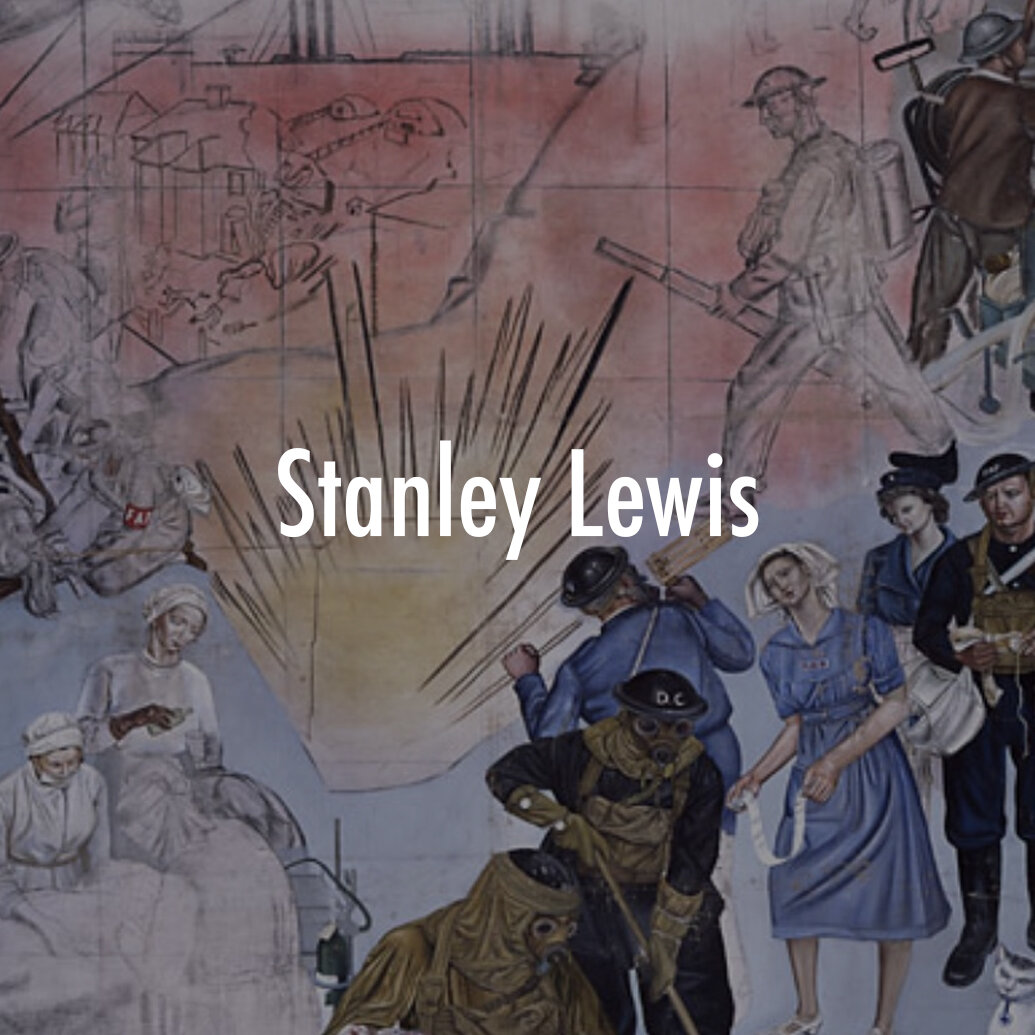

"I’ve been to look at one of our new armament factories - one of those which have sprung up during the last few months in different parts of the country where there was nothing but open fields before. Now it stands in spacious grounds with wide, smooth roads of asphalt leading to it, and it’s turning out anti-tank and anti-aircraft guns.

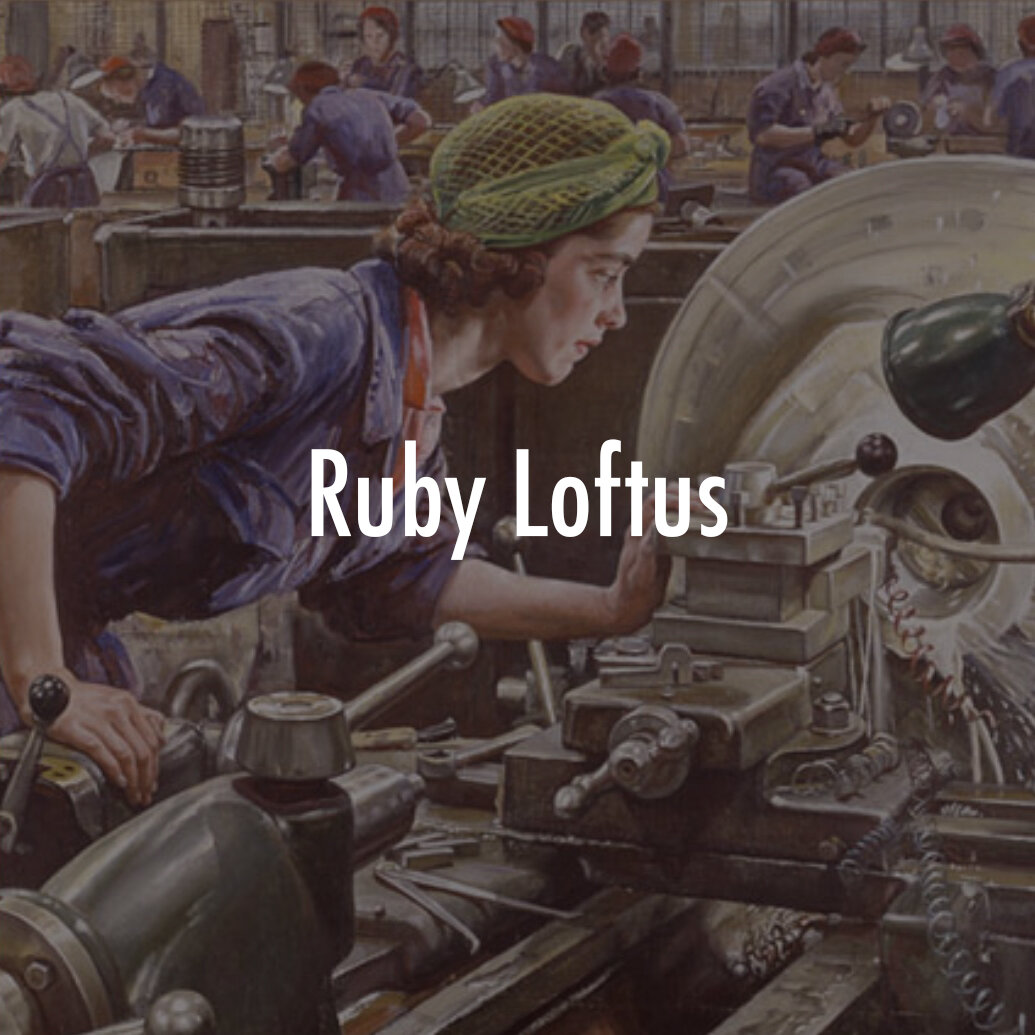

The first, and most lasting impression you get is of brand newness, and youth — you see girls anrd young women in navy blue boiler suits working in long factory bays extending away almost to vanishing point.

Dark blue figures against the creamy-grey concrete floors and brand new wooden benches. They are wearing smart blue “Sister Dora” caps to match their boiler suits, and their curls showing under their caps sway and clasp as they work energetically, filing away at a piece of steel in a vice, or sawing away with a hacksaw.

Dark figures against a cream background tensely alive, with an expression on their faces as if they were playing tennis - or some new game. You see them knitting their brows, and if they glance at you it’s only for a second, and their eyes look very deep, and you can see that they are intensely interested and intrigued in what they are doing - this new work that they are busy with.

They are all girls who are new to this kind of work. Some of them were shop assistants, dress designers, cinema attendants - or just housewives at home - and they’ve come here with the new flood of women into the armament and munition factories.

The womenfolk take the war more seriously even than the men.

All these girls - hundreds of them - are training, or have been trained, during the past few months. I watched some of them who had only been there a fortnight. They were learning how to use a file, a hacksaw, a hammer and chisel, or a punch, how to file straight, not to file low at one end - and they had variously shaped pieces of steel in the vices - they were working at squares, triangles, half-rounds. I talked with some of them and they told me that they liked the work.

Their shoulders were tired when they got home, and they felt tired in their feet, and their legs ached with standing. I noticed that most of them were wearing suede or light leather court shoes.

Clogs

I don’t wonder at them being tired, standing in those shoes on concrete all day, so I recommended clogs. Clogs with wooden soles support the instep, and air can get to your feet. They are cooler in summer and warmer in winter.

I know, as a weaver, when I’ve had my clogs at the mend - as we say when they are being repaired - and I’ve worn shoes for a day, I’ve felt much tireder. If you’re standing up all day you need strong support to your instep. A pair of clogs rests your feet just like putting them on the fender at home.

If you don’t like wearing them in the street you can leave them at your work and change into shoes - most of the girls do this now in the weaving sheds. If the wooden soles are of alder they can be made as light as shoes -or even lighter - and if you don’t like irons you can wear leathers or rubbers. But the irons are quite light and less likely to slip when you are used to wearing them. You get a more positive grip of the ground.

Tilers, for instance, in the North of England, wear iron-shod clogs when working on a roof because they get a more positive grip.

The girls smiled at the idea of clogs but I understand now from the Woman welfare officer that one or two pairs are going to be sent for, as an experiment, and if the girls like them they’ll be able to wear them.

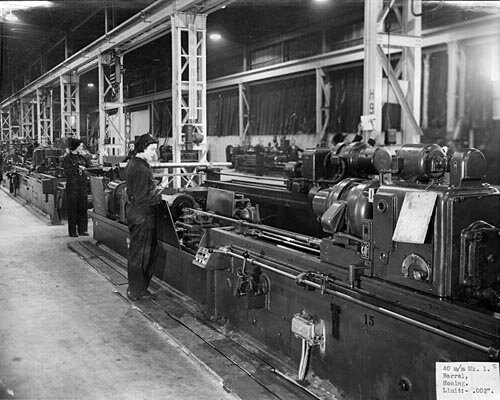

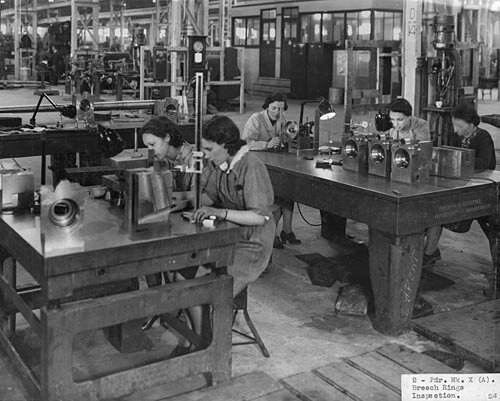

Girls working at machines, in a more advanced stage of training, had stools and were able to sit down part of the time. Some of the processes, once the machine had been set — boring out the barrel of a gun for instance — may take as long as five hours, and they’ve little to do but watch the machines. The girls are very proud of their jobs when they are put on a machine and the learners are impatient to have a machine of their own.

A barmaid's choice

I remember asking one of the girls who was standing by the side of her companion who was teaching her how to handle a drill - her fingers were itching to do it herself - I said to her, “Well, do you think you’ll be able to pick it up?”

“I’ve picked it up,” she said. She’d been a barmaid. “Would you rather do this kind of work?” I said. “Oh yes,” she said, “I have my nights off now.” She didn’t take her eyes off the drill which was rotating in front of her in a milky stream of cooling water, oil and soap.

A few skilled men

Apart from a nucleus of skilled men the factory seemed to be run entirely by women. You see them everywhere, at benches, machines, and on the gantries or travelling cranes which whirr overhead. You can hear machines clicking, hissing, swishing and grinding, and the rasping of the tiles at intervals, and the ringing of steel as somebody drops a tool somewhere on the concrete floor.

And as you walk along the broad alleyways down the bays bits of “swarf” stick into your shoes, sharp steel shavings from the lathes, they stick into your soles - rather an uncomfortable feeling - I had to keep stopping to pick them out.

The girls look very smart in their blue caps with their bright bronze Royal Ordnance Factory badges, but some of them had turned their caps inside out and were wearing them like tam o’shanters or little berets over one eye. They had pinned the badge at the front again, and I’m not sure whether they didn’t look smarter that way — more military — less like a nurse.

"I'm no angel!"

Then a golden-haired girl came down a ladder from one of the gantries. I asked her how she liked it up there, flying in mid-air like an angel over the heads of the others. She looked at me archly and said “I’m no angel, though I have my good points!”

Doing something for the War

She was a junior mistress in a private school, a certificated teacher. Used to teach French and English grammar. Her children have been evacuated.

“What made you come here to work?” I said. “Well,” she said, “I needed money. I want to save up and go to the university sometime. And then — I thought I ought to do something for the war, we all ought to contribute something, spirit if nothing else. I have my ideals - but they’re practical ones.”

Talented musicians

This young woman is one of the star singers at the factory concerts which are held at dinner time in the big canteen several times a week. She sings “Ave Maria” and nearly brings the roof down.

Let me say a word about this factory talent. There are some quite promising artistes and musicians. One of the men, a millwright — and an ex dirt-track racer - is the star comedian. His most popular turn is a parody of Hitler. He makes his moustache from a piece of lathe packing, (a kind of dark-coloured felt which is part of the packing of machinery when it arrives from America), puts on his auxiliary fireman’s jackboots, a coachman’s breeches and a montax coat.

The works has a band composed of two saxophones, two violins, a drum and a piano. The factory choir has been rather broken up by the shifts — the Superintendent concentrates on production first — but when you hear the workers community singing, well, there’s a choir that can’t be broken up, anyway! It’s a real tonic to visit one of these canteen concerts.

Duty

I had a talk with some married women who had come to work at the factory. One of them was a bricklayer’s wife. She’d had a comfortable life at home for sixteen years. “I felt it was my duty to come,” she said. “My husband’s trade is a reserved occupation, and I thank God that I have him at home. I want to do something to win the war. I felt that one of us should go and make a sacrifice. I’ve a son, fifteen - I hope we’ll have won the war before he’ll have to go.”

Another woman was the wife of a Corporation road-sweeper. She has four children, three sons, - aged twenty, thirteen and eight -and a daughter aged fifteen. The daughter now keeps house during the day and gets her father’s dinner ready. As she talked to me she kept her eyes on her work - a long solid-boring machine where she was making the barrel of an anti-aircraft gun.

By her side was another married woman, a younger woman who was learning to do her job (her husband’s away in the army, and her baby is looked after by her parents while she’s at work). Mrs. Hodge, who was teaching her, has been there since the factory was built. There were only six machines and eleven girls, she says, at first. Now there are over seven hundred in that department. She’s watched it grow.

“Only twelve months ago my boys were playing cricket where this factory is,” she said. “It was just fields and there was a pond and a little clay pit full of water, and the boys used to sail planks on it. It’s marvellous how they’ve built all this up in the time.

Tireless Superintendent

The Superintendent never sits down, he’s in the factory all the time. “Do you like your work,” he says to us, and he looks well after us. He goes round in the night just the same. We wonder sometimes when he manages to get his sleep in. He sees to it that we are warm, and that we have hot water and clean towels. And the canteen meals are good considering the prices. You can get a cooked meal for eightpence.

"Get on with the job!"

Mrs. Hodge is fifty-five. She’s volunteered not to take cover during the air raid alerts. “If we’re to be killed, we’ll be killed,” she said. “If we weren’t free as we are now I wouldn’t want to live,” - a philosophy which is now pretty general in this country where people shelter less now than they did.

Get on with the job, and take a chance! It’s a soldier’s philosophy.

Who does the housework?

“But what about the heavier housework, washing and so on?” I said. “Does your little daughter do that?” “Oh,” she said, “I put the clothes to soak one night and wash them the next, and my daughter irons them during the day. She wants to work at this factory but they won’t take girls until they are seventeen.”

When she’d finished work I went home with this woman to look at her house and the garden she’d been telling me about, (she and her husband have won prizes for chrysanthemums which they have grown). She travels to and from her work with the others in buses. She lives in a street in a town — rows of two-storeyed cottages with attics and with little gardens front and back.

The little oblong gardens in front are only about ten feet by four with iron rails on a low brick wall, and a little iron garden gate. Some of the gardens have privet bushes, and there are tiny lawns a yard square surrounded by wallflowers, or pansies, or little marbled stones, and some of them have ferns which have been brought from the woods. Just outside the door in some of the gardens you’ll see a perambulator with a baby in it asleep. The gardens at the back are rather bigger, and as you stand in one of them and look down the sloping street you see little apple trees covered with blossom."

- William Holt

May 20th/21st, 1941