ROF Stories:

Girl on a Motorcycle

Iris Watts was fifteen when she left school and started an apprenticeship at Griffiths, the tailors. She was there until the age of eighteen when all eighteen year olds had to register either for the Forces or work in munition factories.

This is her story.

Girl on a motorcycle

"I wanted to go as a dispatch rider as I had already passed my motorcycle driving test and I had my own bike. In Newport, in the 1930s, I was the first woman to pass my motorcycle test. I had a little two-stroke at first. Then I had a 350cc Ariel – it was heavy. But my mother was ill so I stayed at home to look after her.

My parents had nine children - six boys and three girls. During the war the boys were in all the different branches of the armed forces - air force, navy, reserves - and one was a paratrooper. Renée and Eunice were in the Land Army in Usk.

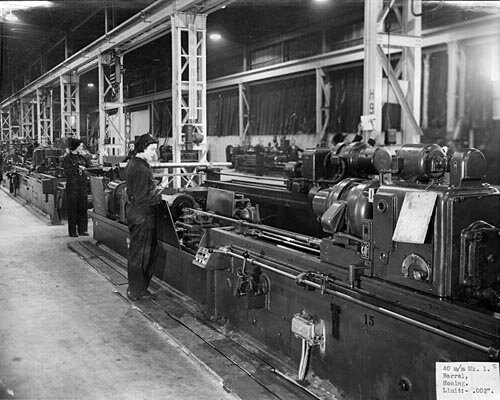

I had to go to the Royal Ordnance Factory for an interview. Then I was put on a training course on how to use a micrometer amongst other things. We did our training at “school” in the Factory for a few weeks then we were put on the benches in the Small Mech. Section.

We had to buy our own navy overalls and we wore a cap or hat. We had a badge and a pass with a photo that we always had to show at the security gate. The gate was manned all the time by the Factory police.

The noise was dreadful

When I went in to the Factory at first I thought the noise was dreadful. I thought I would never stick it after the little tailor’s workshop! But we got used to it over the years.

I was at the ROF for about four years and I enjoyed it all the time I was there. It was hard – two weeks on day shift, then two weeks on night shift, from 8 o’clock to 8 o’clock; twelve hour shifts all the time with an hour’s meal break and tea was brought round. It was not a nice atmosphere; there was no air in the summer. We were packed in and just got on with it.

There was always oil on the floor; you could slip

It was dangerous too – when they wanted to move a gun, the crane came down, took it up and moved it to the next section and then brought in the next gun. I was hit on the head by a gun – it was spinning around in the air and it clobbered me! That Molly the Slinger was a right one! Nobody made any fuss; I think I just went to the "quiet room" for ten minutes. There was always oil on the floor; you could slip.

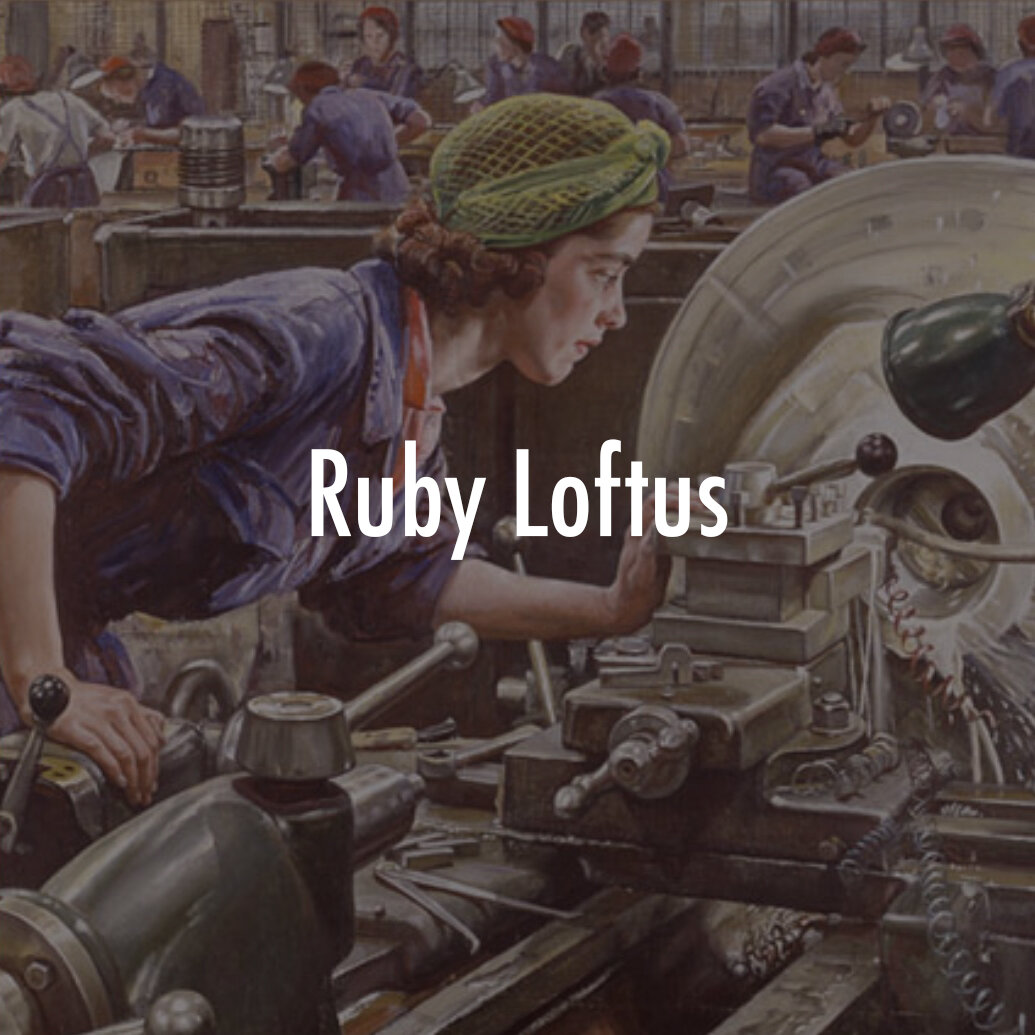

The section I worked in was next to the bay where Ruby Loftus used to work a lathe. When Laura Knight was painting Ruby’s picture, we could see Dame Laura at work. We would go round during the tea break for a chat as she was very friendly, a nice person. She’d chat to you as she painted on the canvas. She sketched first while Ruby carried on working; Ruby didn’t pose. Laura Knight was working for several weeks – but it didn’t make any difference to us!

Filming of Night Shift

When they filmed Night Shift, I happened to be on nights at the time. They came round and asked if we’d mind being filmed. We just went on doing what we did normally and wore our ordinary clothes. They set up the cameras and we carried on. Nothing was organised. It was nothing to get excited about. When the film was released, it was shown in the Factory and Pathé news showed part of it in the cinemas - then we forgot all about it.

It was work, home, sleep, then back again. On the night shift, we came off at 8 o’clock on Saturday morning then started again at eight in the evening on Sunday night. Work, work, work - that’s all you ever did. It was especially hard at the turnover when you changed from day shift to night shift.

Many of the trained men and inspectors came from Nottingham ROF. Most of the women machinists were local and lots of Valleys girls came down by bus and got digs in Newport, many in Corporation Road and Marlborough Road. Lots of girls stayed in that area.

Air raids

We didn’t go to the shelters when there was an air raid. Mostly we didn’t know anything about the raids because of the noise of the machines in the Factory. I was on duty one night when a bomb exploded in a street nearby. I was thrown against the wall by the blast, which was only alongside the Factory. A lot of people in that street were killed.

Cutting the clino was my job. You had to get it perfect for the alignment of the gun. You needed lots of patience – sometimes you’d spend the whole night working on one plate. It was just women doing that job, with men supervisors – the work was so fine.

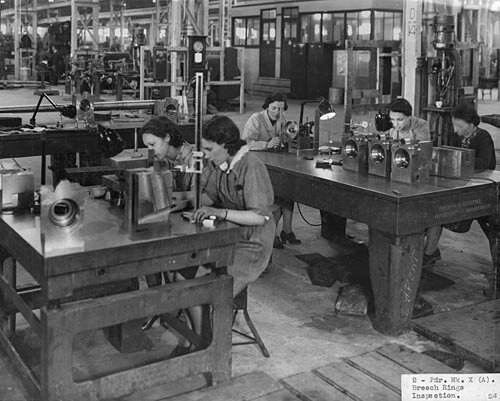

From 1941 I was on the Inspection Bench. That was promotion and I got paid more! For the first fortnight of each month we were not very busy. Sometimes you even got the chance to get some sleep under the counters. During these two weeks, everyone was waiting for the Small Mech. to come through, build up and be collected together. But then for the second fortnight of the month, it was murder! Everyone had to work as hard as they could to get the quota out.

During the bombing in 1940 and 1941, I remember watching the searchlights over Allt-yr-yn and Newport all night. I was fascinated by them. We would hear the drone of the planes, then they would be held in the crossed beams of the searchlights.

Yanks and Woodbines

There were lots of Americans stationed at Malpas at the TA barracks. They were all nice chaps. They never ever approached you unless they knew you. In the blackout it was so dark, all you’d see would was the light of a cigarette. Everyone smoked in the days. I smoked Craven A which came in a little flat box. My mother had a shop that sold cigarettes, little packets of five Woodbine or Park Drive. When she had an order in, I’d take a few round for my friends. They were like gold. I suppose all the cigarettes were being sent abroad for the chaps

I got married in 1942. My husband Bill was a mechanic in the RAF. A week or two after the wedding he was sent overseas. We didn’t know where he was for two months. A lot of people were going out to Italy then. Then we got a postcard from India and we knew he was in Karachi. He didn’t come back for three years.

Gradually at the end of the war, they told us we could finish if we wanted to. My mother was still ill, so I came out in 1945".

- Iris Bowkett (née Watts)

July 2004